What is security posture? A complete guide for organizations

To protect their IT systems, data, and customers from digital threats, organizations benefit from an overall cybersecurity approach. In practice, “security posture” is the umbrella term for how a program holds up across technology, processes, and people, and how well it supports day-to-day defense and incident readiness.

In this article, we’ll break down the various facets of this broad term to show why it’s important. Plus, practical ways organizations can strengthen their security posture based on their risks and operating environment.

Understanding security posture

Security posture is sometimes discussed alongside terms like security maturity, security performance, and security assessment. These ideas overlap, and definitions can vary, but the distinctions below are useful for planning and measurement.

Definition and importance

A security posture can be understood as a snapshot of an organization’s security status across networks, information, and systems, based on the resources and capabilities in place (such as people, hardware, software, and policies) to defend the organization and respond as situations change.

A closely related concept, security maturity, typically describes how developed and repeatable those capabilities are over time, how consistently they’re implemented, measured, and improved as the organization and threat landscape evolve. Security performance is the measured effectiveness of those controls and processes. A security assessment is the act of evaluating systems, controls, or programs to identify gaps and validate effectiveness.

Among other factors, an organization’s security posture is shaped by the effectiveness of its controls and policies, how well assets and configurations are managed, how frequently posture is evaluated, and whether staff training and response plans support prevention, detection, and recovery.

Security posture vs. security strategy

Security posture describes an organization’s overall security status and readiness, while a security strategy is a structured plan for making changes over time. A security strategy typically outlines short- or long-term improvements to systems, controls, and security practices.

As such, implementing a strategy may be necessary to maintain or strengthen a company’s security posture.

Management or IT teams may formulate a security strategy after assessing the present security posture and considering business objectives, budget constraints, regulatory requirements, and the evolving threat landscape.

Executing a security strategy may involve deploying new security technologies, conducting employee training programs, updating policies, or implementing additional controls. These changes can shift the organization's overall security posture over time.

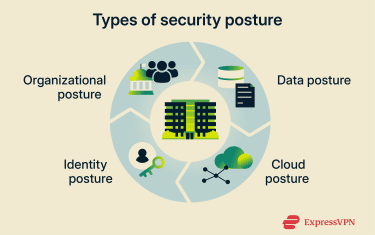

Types of security posture

Many larger organizations manage a complex web of interconnected assets, teams, and operations across diverse IT environments. As a result, security posture often spans multiple domains (for example, organizational, data, cloud, and identity), bringing together people, processes, policies, and technology into an overall view of security readiness.

For this reason, a single organization typically has a posture that encompasses multiple areas.

Security culture (organizational posture)

This covers the people- and process-driven side of security: leadership priorities, governance, and day-to-day habits that determine whether security practices are actually followed. While it’s less about specific technical controls, it strongly influences how consistently those controls are implemented and maintained.

This domain can be assessed with questions like:

- Are security teams adequately funded and staffed?

- Are policies consistently followed and enforced?

- Is executive leadership involved in security governance?

- Do all staff understand their security roles and responsibilities?

- Are stakeholders aligned with or resistant to security initiatives?

If the answers are broadly positive, organizational security posture is likely strong. If obvious problems exist, they can weaken the overall security posture, even if the underlying technical safeguards are robust.

Data security posture

At many companies, data is one of the most valuable assets. For this reason, it’s critical to have a robust data security posture. By protecting data from theft, loss, or exposure, firms may avoid financial or reputational harm.

Many common cybersecurity attacks explicitly target data, such as ransomware and infostealers. Ransomware, in particular, can impact data availability through encryption and may also involve data theft via exfiltration. A strong security posture should account for these risks.

Regulations often influence how data is used, protected, stored, and handled, especially when organizations process sensitive customer information. Requirements vary by jurisdiction and industry, but legal and contractual obligations are often a factor.

To get a rough assessment of a company’s data security posture, consider asking:

- Do relevant parties know where sensitive data is stored and how it flows between systems and third parties?

- Is sensitive data encrypted and governed with clear handling, retention, and sharing rules?

- Is access to sensitive data limited using least privilege and zero trust principles (where applicable)?

- Are systems in place to detect and respond to signs of exfiltration?

- Are reliable, tested backups in place to support recovery from ransomware or accidental loss?

Positive responses suggest healthier data security controls and governance. Negative responses point to gaps that warrant follow-up review and remediation.

Cloud security posture

Many companies today rely on hybrid cloud or multi-cloud ecosystems. This may involve various combinations of private and public cloud deployments. Frequently, these interact with on-premise infrastructure.

Organizations also commonly use Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), and other cloud services for daily operations. Because responsibilities and controls can differ across cloud service models and providers, maintaining consistent protections across environments can expand the attack surface, especially when visibility, configuration, and identity controls vary.

Misconfigurations between cloud services are a common source of vulnerabilities. Attackers also target third-party services and dependencies as entry points for supply chain attacks.

Cloud security posture centers on cloud configuration, governance, identity and access control, and exposure risks across cloud systems. Enforcing baseline security levels across a potentially vast and expanding network is essential to maintaining a strong security posture.

To assess cloud security posture, consider the following:

- Is there a complete, up-to-date inventory of cloud services, accounts, and resources across all environments?

- Are secure baseline configurations consistently enforced across cloud platforms?

- Are misconfigurations and publicly exposed assets quickly detected and remediated?

- Are cloud identities, API keys, and service-to-service access monitored and controlled?

- Are third-party cloud services and integrations assessed for security risks?

If most of these questions can be answered affirmatively, it signals a strong cloud security posture. On the other hand, any negative responses are worth investigating, since cloud risks often scale quickly across interconnected services.

Identity and access management (IAM)

Identity determines who can access systems and what they can do. Managing identities and their permissions becomes significantly more challenging in complex IT environments. With weak identity and access controls, an organization becomes vulnerable to a wide range of threats.

Many companies need to manage identities across on-premises, cloud, and hybrid work environments. This has shifted the focus from maintaining a secure network perimeter to managing identities, access privileges, and authentication controls.

How an organization handles IAM is a key part of its overall security posture. These practices influence how well it prevents unauthorized access to resources while supporting legitimate use.

To assess the strength of an entity’s IAM, relevant questions may include:

- Can systems and IT staff monitor for suspicious sign-in and access behavior?

- Are misconfigurations and overprivileged accounts regularly checked for?

- Are service accounts and API keys securely managed (and shared user accounts avoided where possible)?

- Are IAM policies consistently enforced (provisioning, deprovisioning, and access reviews)?

- Are strong authentication controls in place, such as multi-factor authentication (MFA), and credential protections?

Affirmative answers suggest a strong identity security posture, while negative responses highlight areas for improvement.

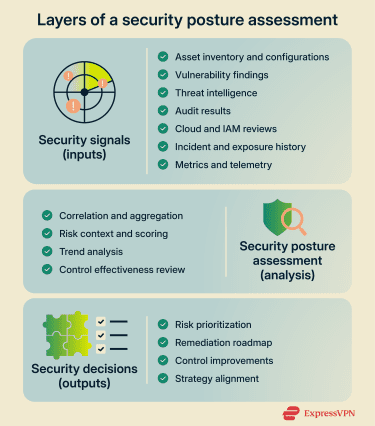

How to assess your security posture

Organizations conduct security posture assessments to determine whether current security conditions align with overall goals. Without regular assessments and validation, it’s difficult to know how well controls and processes are working in practice.

Assessors typically incorporate findings from recent security audits into posture analysis, alongside more targeted technical and risk-focused reviews. Regular assessments are vital because the threat landscape is constantly evolving, and changes in staff, business priorities, and IT systems can introduce new risks.

Security posture assessments give security teams an opportunity to evaluate whether the current security posture is sufficient. They can often uncover new risks and confirm areas of improvement.

Security posture assessment process

The first step is to clearly outline how assessments will be conducted and define the scope. The exact process and systems to be considered may vary significantly between organizations.

That said, most security posture assessments include some version of the following:

- Asset inventory: Build a complete view of systems, services, data, and other assets that require protection.

- Vulnerability assessment: Identify weaknesses such as misconfigurations, control gaps, and known vulnerabilities. Techniques typically include penetration testing, manual analysis, or automated vulnerability scanning.

- Threat analysis: Identify relevant threat sources/events and how they could exploit weaknesses, informed by broad trends and organization- or sector-specific risks.

- Compliance reporting: Evaluate alignment with applicable laws, regulations, and internal guidelines. This usually involves examining current practices and comparing them with documented standards.

- Security controls review: Verify that essential controls are implemented and operating effectively. For example, endpoint protection, network controls, access controls, and zero-trust principles were adopted.

- Incident response readiness: Test whether an organization can detect, contain, and recover from cyberattacks. This may involve using methods such as tabletop exercises, plan reviews, and (where appropriate) red teaming or penetration testing, followed by a review of performance and gaps.

Key metrics to evaluate

When assessing a company or organization's security posture, analysts typically gather measurable evidence, supported by assessment findings and control validation. The exact metrics to look for vary by organization/environment, but a few broad categories can cover many of the common indicators.

- Vulnerability and exposure metrics: Total known vulnerabilities, percentage of critical vulnerabilities unresolved, average time to patch, and number of assets exposed to the public internet.

- Threat detection metrics: Alert volume and severity mix, false-positive rate, mean time to detect suspicious activity (MTTD), coverage across endpoints and networks, and visibility into lateral movement

- Incident response metrics: Mean time to acknowledge/triage, respond/contain, and recover, tracked as separate time-to-X measures. This is often grouped under mean time to respond (MTTR), depending on how it’s defined.

- IAM metrics: Number of privileged accounts, extent to which MFA is used, volume of dormant or orphaned accounts, and policy violations tied to excessive or misused permissions.

- Human risk/error metrics: Phishing simulation outcomes, security training completion rates, incidents tied to user error, and frequency of policy violations.

Security posture management

Managing security posture across modern environments takes ongoing visibility and prioritization. Specialized tools can help surface posture risks and speed up remediation.

Tools for security posture management

Security posture management (SPM) tools help security teams track and address issues. Common tool categories include:

- Data security posture management (DSPM): Focuses on data risks such as discovery, classification, access exposure, and compliance gaps. These tools help teams understand where sensitive data lives, who can access it, and what controls are missing or misconfigured

- Cloud security posture management (CSPM): Provides continuous visibility into the security state of cloud assets and workloads. CSPM is commonly used to detect misconfigurations, enforce baseline policies, and prioritize cloud posture risks across environments.

- Identity security posture management (ISPM): Provides visibility into identity lifecycles across on-premise and cloud environments. This includes detecting misconfigurations and risky access patterns, and weak authentication coverage.

- Security information and event management (SIEM): Aggregates and analyzes security data from systems and tools, presenting it as actionable information that often supports the detection and investigation of anomalous activity. While not a core SPM category, SIEM data can support posture work by providing evidence of control effectiveness and suspicious behavior.

- Security orchestration, automation, and response (SOAR): Automates and orchestrates incident response workflows by integrating tools, standardizing playbooks, and streamlining response actions. SOAR can support posture improvements by helping teams respond faster and apply consistent remediation processes.

Best practices and frameworks

Organizations often use well-established frameworks and standards to assess and manage their security posture. These resources provide high-level guidance and a common language for planning, measuring, and improving cybersecurity.

Like SPM tools, organizations may use multiple frameworks to support different areas of their security posture. Common examples include:

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework (CSF): A widely used framework from NIST that helps organizations understand, assess, prioritize, and communicate cybersecurity risk. CSF 2.0 was released in 2024.

- Center for Internet Security Critical Security Controls (CIS Controls): A prioritized set of best practices organized into 18 Controls (current release is v8.1) to help organizations reduce common attack paths and strengthen cybersecurity hygiene.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) / International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 27001:2022: A standard that specifies requirements for establishing, implementing, maintaining, and continually improving an information security management system (ISMS), supporting information security, cybersecurity, and privacy protection.

Further, many organizations must meet legal and regulatory requirements, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). They may also be bound by industry standards and contractual obligations, for example, the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) for payment card environments.

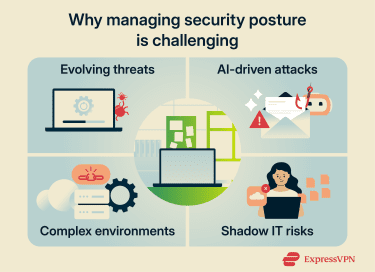

Security posture risks and challenges

Developing a cybersecurity strategy for a large organization is challenging. Beyond the inherent complexity, specific issues present additional problems.

Evolving threat landscape

The cybersecurity landscape is constantly changing. Threat actors adopt novel tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), develop new malware, and refine attack chains. Objectives and targeting can also shift as technology and defensive practices change.

New vulnerabilities and misconfigurations can also appear as organizations update, reconfigure, or expand IT systems, and some previously unknown flaws may be exploited as zero-day attacks.

This is why organizations should avoid treating security as a static concern. To maintain a strong security posture, it’s important to adapt to internal changes and an evolving external threat landscape.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning

Many organizations are integrating AI and machine learning into their security programs, but these tools also introduce risks. Threat actors are also using generative AI to support activities such as social engineering and reconnaissance, which can increase scale and realism in common attack techniques.

Attackers may also use AI-enabled tooling to speed up the discovery of weaknesses or improve targeting. In response, many organizations are exploring defensive uses of AI, but limited resources or expertise can make effective deployment difficult.

AI-driven defenses can also introduce new attack paths, for example, through poisoned models or compromised AI-related dependencies in the software supply chain.

Shadow IT

Shadow IT refers to technology used within an organization without the IT department's approval or proper oversight. It can include apps, devices, data stores, and accounts that may be benign or risky, but the lack of visibility creates blind spots that attackers can exploit.

The risk posed by shadow IT increases as an organization’s digital asset inventory grows and its technology becomes more diverse. The more endpoints in the organization are exposed to external networks, the more shadow data may be exfiltrated unknowingly. Similarly, inadequate offboarding may leave an ex-employee with access to critical assets. These gaps can negatively affect the overall security posture.

FAQs: Common questions about security posture

What are the components of security posture?

Key security posture components include asset inventory, risk management, vulnerabilities and threat management, employee training and awareness, governance and compliance, security controls, and incident response readiness. Together, these elements help reduce the likelihood and potential impact of cybersecurity incidents.

How often should you assess security posture?

Frequency depends on the organization’s security maturity, strategy, and operational needs. Some businesses run comprehensive assessments quarterly, especially in high-change or regulated environments, while others assess annually and rely on continuous monitoring in between. In any case, assessments should be done at a frequency sufficient to inform risk-based decisions.

How does security posture affect compliance?

Compliance is one component of an organization’s security posture. Organizations may need to meet legal and regulatory requirements, especially regarding data protection, depending on jurisdiction, industry, and business activities. Standards and certifications can also help demonstrate security practices to stakeholders and build confidence with customers, partners, and clients.

What are the consequences of a weak security posture?

The consequences of a weak security posture often include a higher incidence of security breaches, slower incident response, and less effective remediation. Organizations that don’t adequately understand their security posture can also misallocate cybersecurity resources, wasting time, leaving vulnerabilities unaddressed, and struggling to adapt to changing threats.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN