What is the CVE database and how does it work?

The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database plays a central role in how the cybersecurity industry tracks and communicates software flaws. It allows security researchers and vendors to discuss new vulnerabilities and assess their impact in real-world scenarios.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at how the CVE database works, the role of the National Vulnerability Database (NVD), and how you can effectively use CVEs in vulnerability management.

What is the CVE database?

The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database is a public catalog of known security vulnerabilities. It serves as a central registry for vulnerabilities that have been publicly disclosed and documented within the cybersecurity community.

The CVE list was introduced in 1999 by the MITRE Corporation, a U.S.-based nonprofit organization that works with government and industry on cybersecurity and critical infrastructure initiatives. Today, MITRE Corporation is still responsible for operating and maintaining the CVE program.

Why the CVE database exists

The CVE program was created to address a fundamental coordination problem in vulnerability management. In the late 1990s, security tools and vendors maintained their own vulnerability lists and naming schemes, so they often ended up using different names for the same issue. This made it difficult to correlate findings, assess impact, or ensure remediation was complete.

CVE introduced a shared identifier system to solve this problem, allowing vulnerabilities to be referenced consistently across tools, advisories, and organizations.

What happened to “Exposures” in CVE?

Although the name CVE references both vulnerabilities and exposures, the distinction between the two never fully took hold in practice. The original definition separated universal vulnerabilities from exposures:

- A universal vulnerability: Something that would be considered a vulnerability under any reasonable security policy. For example, flaws that allow code execution, unauthorized data access, impersonation, or denial of service (DoS).

- An exposure: A system state or capability that doesn’t immediately compromise security, but still increases risk under some reasonable security policies, such as information-leaking services, weak configurations, or components that behave as designed but are easy to abuse.

However, CVE records were never labeled or categorized using this distinction. In practice, all entries are treated as vulnerabilities, and CVE essentially functions as a vulnerability tracking system.

How the CVE system works

The CVE system assigns each vulnerability a unique identifier and publishes a minimal record.

CVE IDs and naming format

A CVE ID is a unique identifier assigned to each vulnerability in the CVE list. Every CVE ID follows a standardized format: CVE-YYYY-NNNN (for example, CVE-1999-0067), where:

- CVE is a fixed prefix used for all entries.

- YYYY represents the year the CVE ID was assigned (not necessarily the year the vulnerability was discovered).

- NNNN is a numeric sequence that uniquely identifies the vulnerability within that year.

Originally, the numeric portion was limited to four digits, allowing for up to 9,999 CVE IDs per year. In 2014, the format was expanded to allow five or more digits, removing this limitation.

How vulnerabilities are assigned CVEs

Vulnerabilities are assigned CVE IDs by organizations known as CVE Numbering Authorities (CNAs), which are entities authorized by the CVE program to assign CVE IDs within a defined scope. These can include software vendors, security researchers, open-source projects, hosted services, computer emergency response teams (CERTs), and other coordination bodies.

Each CNA is responsible only for vulnerabilities within its assigned scope, which helps prevent duplicate or conflicting CVE assignments. Depending on the nature of the vulnerability and who is responsible for the affected product, different types of CNAs may be involved:

- Supplier CNAs: Assign CVEs for products they own, develop, and maintain

- Researcher or coordinating CNAs: Handle vulnerabilities affecting multiple vendors or cases where no single supplier owns the issue

- The CNA of Last Resort (CNA-LR): Assigns CVEs when no appropriate CNA can be identified, such as when a vendor no longer exists or declines responsibility

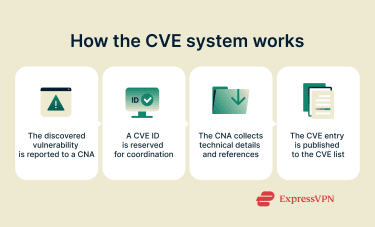

The CVE lifecycle from discovery to publication

A vulnerability within the CVE program moves through various stages before it’s finally published.

When a vulnerability is first discovered, it gets reported to a CVE program partner with a request for a CVE identifier. The CVE partner then assigns a CVE ID, which enters the Reserved state. This means the CVE ID is used for early-stage vulnerability coordination but is not yet ready to be publicly disclosed.

The CVE program partner then collects details such as affected or fixed product versions, root cause, vulnerability type, impact, and at least one public reference. Once the minimum required data is collected, the CVE ID is included in a CVE record and published to the CVE list by the relevant CNA.

In some cases, a CVE entry may be marked as Rejected when it’s considered invalid (for example, due to duplication) or Disputed when there is disagreement between two or more parties about whether it qualifies as a vulnerability.

What information does a CVE entry contain?

A published CVE entry typically includes:

- The CVE ID, which serves as the global identifier.

- A brief description of the vulnerability, including affected products and versions.

- One or more external references, such as vendor advisories or research write-ups.

- Information about the CNA that assigned the CVE ID.

Common misconceptions about CVE

Here are some common myths about the CVE program.

“All CVEs are serious”

Not every vulnerability assigned a CVE ID is high impact. A CVE simply indicates that a vulnerability exists and has been publicly documented. Its real-world severity depends on factors such as the affected environment, system configuration, and asset exposure.

“A CVE gives a vendor a bad reputation”

The presence of CVEs in a product does not reflect poorly on a vendor. In many cases, it demonstrates responsible security practices, including vulnerability disclosure, transparency, and timely remediation. Mature vendors routinely publish CVEs as part of normal security operations.

“Obtaining a CVE ID takes a long time”

While the CVE process includes multiple stages, assigning a CVE ID is often faster than expected. Once sufficient information is available and the request falls within a CNA’s scope, CVE IDs are frequently issued within days rather than months.

“MITRE assigns CVSS scores”

The CVE program doesn’t assign severity or risk scores. Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) scoring is performed separately, most commonly by the NVD as part of its enrichment process.

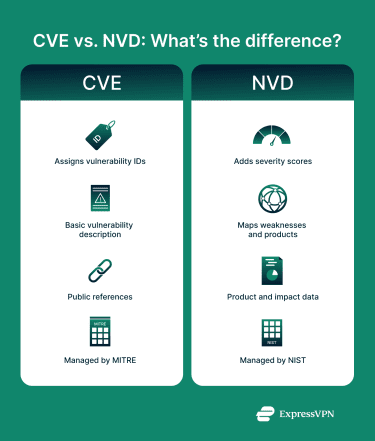

CVE Database vs. NVD: What’s the Difference?

The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) is the U.S. government’s repository of standardized vulnerability management data, maintained by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The NVD builds on CVE entries and enriches them by adding more information about the vulnerabilities.

What the NVD database adds

Metrics

The NVD adds a CVSS score to each vulnerability, indicating its severity. Scores range from 0.00–10.00, with higher scores representing greater severity. The score is based on factors such as exploit complexity, required privileges, user interaction, affected components, and confidentiality, integrity, or availability (CIA) impact. However, CVSS is not a measure of risk.

Weakness Enumeration

The NVD maps each CVE entry to its corresponding Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE). CWE is a list of known software and hardware weaknesses that can lead to vulnerabilities. Like CVE, CWE is also maintained by MITRE. The NVD maps CVEs to relevant CWEs to categorize CVE entries, helping identify root causes and enabling indexation based on weakness type.

Known affected software configurations

The Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) dictionary is a standardized naming format for IT products, packages, and software based on the generic syntax for Uniform Resource Identifiers (URI). The NVD uses this CPE dictionary to show which products or software are considered vulnerable at the time of enrichment.

This includes vendor and product names, operating systems and software versions, and updates. This mapping also makes it possible for users to search for NVD entries based on products. For instance, you can find all CVEs affecting a specific Windows version in one place.

How CVE and NVD work together

CVE and NVD play complementary roles in vulnerability management. CVE serves as the authoritative source for identifying and naming vulnerabilities by assigning a CVE ID and providing a brief, neutral description with a public reference. The NVD builds on this foundation with additional context, including severity scoring, affected product data, and weakness classifications.

In short, CVE answers what the vulnerability is, while NVD helps explain how severe it is and what it affects.

How to search for and use CVE entries

You can search for and track vulnerabilities through both the CVE and NVD websites. Use CVE when you need identification and references, and use NVD when you need severity, impact, and product context.

Finding specific CVEs

The most direct way to look up a vulnerability in the CVE database is to type in the CVE ID in the CVE search bar. Entering an exact identifier (for example, CVE-2026-21265) into the CVE website returns the core CVE record, including a brief description and public references.

Searching for the same CVE ID in the NVD provides additional context, such as CVSS severity scores, CWE classifications, and affected product data. The NVD also supports more advanced filtering, including search by publication date, vulnerability status, CNA, and data type.

Tracking CVEs relevant to your software

If you don’t know a specific CVE ID, you can search by product or vendor name. Entering a software name into the CVE database returns a list of CVEs associated with that product. This can be useful for gaining a high-level view of known vulnerabilities affecting a given application.

The NVD offers similar product-based searches, with the added benefit of structured product mappings. You can further filter these results to focus on specific versions, operating systems, or severity levels, making NVD more suitable for impact analysis and vulnerability management workflows.

Understanding CVE risk in a real-world context

A CVE describes a vulnerability in abstract terms, but its real-world risk depends heavily on where and how it appears. Security teams need to understand this gap in order to prioritize remediation effectively instead of treating every CVE the same.

Why the same CVE affects organizations differently

The same CVE can pose very different levels of risk across organizations because CVSS base scores don’t account for industry context, asset criticality, or defensive controls.

The Environmental metric in CVSS allows organizations to adjust severity based on their own priorities, particularly the CIA requirements of their systems.

For example, confidentiality carries extreme importance in a healthcare environment but far less weight for a public information website. So, for example, a CVE with a base score of 7.0 could be evaluated at 9.0 in a healthcare environment and 5.0 in a public library environment.

When a critical CVE may not be urgent

A critical CVE may not be urgent when it can’t realistically be exploited in your environment. This typically happens in a few clear scenarios:

- No active exploitation: Many critical CVEs never see real-world exploitation. If a vulnerability does not appear in the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog and lacks reliable exploit code, it may not require immediate action.

- The affected component isn’t exposed: If the vulnerable service isn’t internet-facing, runs behind strict access controls, or is disabled entirely, the practical risk drops significantly.

- Compensating controls reduce exploitability: Strong controls such as network segmentation, zero-trust enforcement, strict authentication, and monitoring can prevent exploitation even when a vulnerability exists.

- The vulnerability affects unused functionality: Some CVEs target optional features or configurations that are not enabled in your deployment, making exploitation impossible.

When a low-severity CVE can still carry risk

A low-severity CVE becomes dangerous when attackers can combine it with other weaknesses to achieve a larger goal. This commonly happens in the following situations:

- Vulnerability chaining: Attackers often link multiple low- or medium-severity vulnerabilities to move laterally, escalate privileges, or exfiltrate data. Individually, minor issues can become critical when used together.

- Initial access vectors: Low-severity vulnerabilities frequently provide reconnaissance, limited access, or information disclosure that attackers use as a foothold for more serious exploitation.

- Exposure of sensitive environments: Even a low-impact vulnerability can pose a serious risk if it exists on systems that handle sensitive data or have elevated trust relationships.

- Automation and scale: Attackers could exploit low-severity flaws at scale using automated tooling, turning small weaknesses into widespread incidents.

Real-world attacks often rely on lower-severity vulnerabilities as building blocks rather than standalone exploits.

Using CVEs in vulnerability management

CPE mapping

The first step in vulnerability management is determining whether a CVE actually affects your environment. Teams do this by mapping CVEs to CPEs from the NVD, which define the specific vendors, products, and versions impacted by a vulnerability.

They typically rely on vulnerability scanners and asset inventory tools that detect the software running in an environment, identify its vendor, product, and version, and then compare that information against the CPE list. When a match is found, the tool flags the CVE as applicable; when no match exists, the CVE is filtered out as irrelevant.

Using the Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS)

After confirming that a CVE applies to the environment, teams need to understand how likely it is to be exploited. Instead of relying solely on CVSS severity scores, security teams can use the EPSS, developed by the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST).

EPSS uses machine-learning models that analyze a large set of variables to estimate exploitation likelihood. Each CVE receives two EPSS values:

- EPSS Probability: The likelihood that a CVE will be exploited in the next 30 days, expressed as a value between 0 and 1.

- EPSS Percentile: The relative ranking of a CVE compared to all others, also between 0 and 1, where higher values indicate higher exploitation likelihood.

Using SLAs for patch management

Putting everything together, patch management teams should prioritize CVEs that both affect their environment and have high EPSS scores. Modern vulnerability scanners can limit findings to relevant CVEs and create Service Level Agreements (SLAs) in ticketing systems tied directly to CVE IDs.

Each SLA defines a remediation timeframe based on urgency. For example, critical CVEs with high exploitation likelihood may require patching within 24–72 hours.

Teams commonly track SLA performance using mean time to remediate (MTTR), which measures the time between when a CVE is identified and when it is patched. High MTTR values for critical or high-risk CVEs indicate remediation delays and may trigger SLA noncompliance.

Limitations of the CVE system

While the CVE database offers the benefits of standardization, it has a few notable shortcomings.

Why not all vulnerabilities receive CVEs

The CVE program only assigns IDs to issues that meet its definition of a vulnerability: a weakness in a product that can be exploited and impact CIA. Issues that fall outside this scope do not qualify for a CVE ID.

CVE does not assign IDs to certain categories of issues, including:

- Conditions that do not pose a security risk.

- Non-default configurations that are well-documented and understood.

- General attack techniques such as brute-force or high-volume DoS attacks.

- Bypassing detection without exploiting an underlying weakness.

In addition, CVE requires public disclosure. A vulnerability must be documented in a publicly accessible source, such as a vendor advisory, security blog, or disclosure notice, to receive a CVE ID. Internal findings, privately reported bugs, or issues kept under non-disclosure do not qualify. Without public disclosure, the coordination role CVE is designed to serve does not apply.

Delays, backlogs, and incomplete records

CVE publication doesn’t guarantee timely or complete enrichment. While CVE IDs may be issued quickly, much of the additional context security teams rely on, such as severity scores, product mappings, and classifications, comes from the NVD and requires separate analysis. Because this enrichment happens after CVE publication and depends on available resources and review time, it often arrives later and may even.

FAQ: Common questions about the CVE database

How often is the CVE database updated?

The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database is updated as soon as a record is published. Meanwhile, new CVE IDs typically become available in the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) dataset within an hour of publication. After the record is added, the NVD begins enriching it. The enrichment process usually takes longer and varies by CVE.

Who maintains the CVE database?

The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database is maintained by MITRE and funded by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

However, other stakeholders are also involved in the vulnerability assessment process, such as CVE Numbering Authorities (CNAs), which assign CVE IDs within their scope. The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) also plays a role by enriching CVE entries with additional data, such as Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) scores and Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) tags.

What’s the difference between a CVE and a vendor advisory?

A Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) entry is a standardized identifier for a publicly disclosed vulnerability and serves as its universal reference. It contains the name of the vulnerability, a brief description, and at least one public reference.

A vendor advisory, on the other hand, is a more detailed document explaining the vulnerability’s root cause, threat, impact, and available fixes. Also, CVEs are published and maintained by MITRE, vendor advisories are issued by product vendors for specific vulnerabilities.

Do all vulnerabilities get a CVE ID?

No, not all vulnerabilities receive a Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) ID. Only publicly exposed vulnerabilities that impact confidentiality, integrity, or availability (CIA) and fall within the scope of a CVE Numbering Authority (CNA) can be assigned an ID.

Is the CVE database free to use?

Yes, the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database is completely free to use. The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) dataset, which enriches CVE entries, is also free to use.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN