What is the Stuxnet virus and why does it matter?

Stuxnet was an unprecedented piece of malicious software that forced the cybersecurity world to rethink what cyberattacks could achieve. Its discovery revealed a level of planning, resources, and precision rarely seen in malware at the time.

In this guide, we explore what Stuxnet is, how it worked, and why it still shapes modern cybersecurity and industrial defense strategies.

What is the Stuxnet virus?

Despite being commonly referred to as such, Stuxnet isn't a computer virus in the technical sense. It was a self-propagating worm, which is a type of malicious program that can spread independently without attaching itself to files or requiring user interaction.

Stuxnet was reportedly first identified in June 2010, after a Belarusian cybersecurity firm, VirusBlokAda, was asked to investigate a series of unexplained system crashes on computers in Iran. According to security analysts, Stuxnet had been active for months, and possibly years, before its discovery, spreading quietly and largely unnoticed.

How Stuxnet differs from traditional malware

Traditional malware usually spreads as widely as possible, infecting any system it can reach. Stuxnet behaved very differently. It carefully examined each system it encountered and activated only when specific technical conditions were met. If those conditions weren’t present, the malware remained dormant or removed itself, reducing the risk of detection.

This selectivity was paired with an unusual level of sophistication. Stuxnet combined multiple advanced techniques, including previously unknown vulnerabilities (zero-day exploits), trusted digital certificates, and coordinated behavior across systems, into a single operation. This required resources, expertise, and time generally considered beyond those available to typical criminal groups, particularly at the time.

Finally, Stuxnet focused on control rather than immediate destruction. Instead of crashing systems, encrypting data, or cyber extortion, it subtly altered machine behavior over time. This made the attack harder to detect, harder to diagnose, and far more effective in achieving its objective.

How Stuxnet worked

Stuxnet was engineered to interfere with physical processes, not just digital systems. To do this, it targeted programmable logic controllers (PLCs), which are specialized microprocessor-based devices used to control machinery such as motors, pumps, and valves in industrial environments.

PLCs are a critical component of supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, which are used to monitor and manage large-scale industrial operations. Stuxnet specifically targeted Siemens Step7 software, which is widely used to program these controllers. It was designed to modify instructions sent to these controllers, altering how connected machinery operated.

The worm was structured as a multi-stage operation. It first established itself on standard Windows systems and then checked for a very specific industrial environment. Only when those conditions were met did it activate its industrial payload; otherwise, it remained inactive.

How Stuxnet reached its target and infected systems

While the precise method remains unconfirmed, the design of the worm assumed real-world access rather than purely remote compromise. According to cybersecurity firm Symantec’s W32.Stuxnet Dossier (one of the first comprehensive technical reports analyzing the worm), the malware was introduced via infected removable media, possibly through contractors or personnel with legitimate access to restricted environments.

Further analysis showed that to infect the system, Stuxnet exploited four previously unknown vulnerabilities in Microsoft Windows, allowing it to propagate through removable media and internal networks, including systems that weren’t connected to the internet.

Stuxnet also relied on stolen digital certificates issued to legitimate companies. By signing its components with these certificates, the malware was able to appear as trusted software to Windows systems, reducing security warnings and helping it evade detection during installation.

Is Stuxnet still a threat today?

Stuxnet is no longer considered an active widespread threat. Its highly specialized design targeted particular industrial control systems (ICS) that have since been upgraded, patched, or decommissioned.

Notably, Microsoft issued security updates in 2010 (MS10-046 and MS10-061) to patch the vulnerabilities Stuxnet exploited, while certificate authorities, including Verisign, revoked trusted certificates used by Stuxnet’s components.

Why was Stuxnet considered so dangerous?

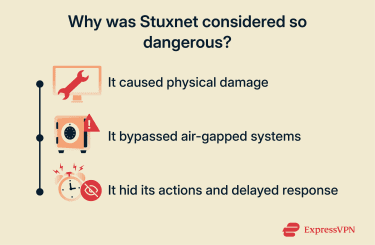

Stuxnet was considered dangerous because it revealed new categories of risk, including technical, operational, and strategic, that hadn’t previously been demonstrated by malware.

It caused physical damage

Stuxnet demonstrated that a cyberattack could cause physical damage while appearing indistinguishable from routine equipment failure. Rather than triggering alarms or system crashes, the effects unfolded gradually, making the damage harder to recognize and diagnose.

This was dangerous because it challenged the assumption that cyber incidents would be visible as cyber incidents. For the first time, software-induced sabotage could blend into normal operational noise.

It bypassed air-gapped systems

Many critical SCADA systems are protected by being “air-gapped,” meaning they are physically separated from the internet and other networks. The idea is simple: If a system has no internet access and no reachable IP address, attackers shouldn’t be able to reach it remotely.

Stuxnet challenged that assumption. It managed to cross this physical gap by spreading through removable media such as USB drives and then moving between trusted machines inside the isolated environment.

It hid its action and delayed response

Stuxnet not only reached protected systems, but it also hid its actions exceptionally well once inside. While manipulating industrial equipment, the malware fed false feedback to monitoring systems, allowing operators to see normal readings even as damage was occurring.

This deception significantly delayed detection and diagnosis. Engineers had little reason to suspect a cyberattack, as the systems appeared to be functioning correctly. As a result, the malware was able to operate for extended periods, amplifying its impact.

Who created Stuxnet and why?

No individual, organization, or government has publicly claimed responsibility for the creation of Stuxnet. However, cybersecurity analysts widely agree that the malware’s unprecedented sophistication, scale, and specificity place it beyond the capabilities of typical criminal or activist groups.

Based on technical analysis and circumstantial indicators, many experts have assessed that Stuxnet appears consistent with the resources and capabilities of a state-sponsored program, and it’s often cited in discussions of early cyberwarfare due to its scale and real-world impact.

How Stuxnet was linked to events in Iran

Stuxnet was linked to events in Iran through a combination of on-site observations at nuclear facilities and subsequent analysis by independent security researchers. Neither Iran nor any alleged perpetrators have officially acknowledged responsibility for such an operation.

According to reports by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), inspectors visiting Iran’s Natanz uranium enrichment facility in 2009 and 2010 observed an unusually high number of centrifuges being taken offline or replaced. The failures appeared inconsistent with normal operational wear, but there was no clear cause publicly identified at the time.

Several cybersecurity researchers later noted that these failures coincided with the presence of the Stuxnet malware. Symantec’s detailed analysis (as published in its aforementioned W32.Stuxnet Dossier) provided key evidence that Stuxnet was designed to specifically target Siemens Step7 PLCs used in the centrifuges, suggesting the worm was designed to cause effects consistent with the disruptions observed at Natanz.

Stuxnet’s legacy and related malware

Stuxnet left a lasting mark on how experts think about digital threats.

Evolution of cyberweapons

Stuxnet is widely cited as accelerating the shift from simple hacking tools to carefully engineered cyberweapons. These newer threats are designed with a clear objective, tested extensively, and often built to avoid detection for long periods of time.

Over time, cyberweapons have become more modular and flexible, meaning parts of their code can be reused or adapted for new purposes. This evolution reflects a broader trend where software is treated as a strategic asset, similar to traditional military technology, but deployed quietly through digital channels.

Notable derivatives: Duqu, Flame, and others

After Stuxnet was uncovered, researchers began finding related malware that shared similar design ideas and coding techniques. These programs weren’t exact copies of Stuxnet, but they followed the same philosophy of precision and stealth. Notable examples include:

- Duqu: Focused primarily on gathering information rather than causing disruption. It included a keylogger, the ability to capture system information, and tools to steal sensitive documents, all designed to support further attacks or espionage.

- Flame: A highly sophisticated spying tool capable of recording audio, capturing screenshots, logging keyboard input, monitoring network traffic, and gathering documents.

- Gauss: Malware designed for financial espionage, able to steal online banking credentials, collect cookies and passwords, and track social media activity.

Stuxnet’s influence on modern cybersecurity

Stuxnet changed how organizations approach security, especially in environments that control physical processes. Before it, most malware was seen as a problem for personal computers and business networks. After Stuxnet, it became clear that software could be used to influence complex systems.

Today, security planning often assumes that highly advanced threats exist, even if they are rarely seen. Stuxnet helped shift the mindset from reacting to obvious attacks to preparing for quiet, long-term ones.

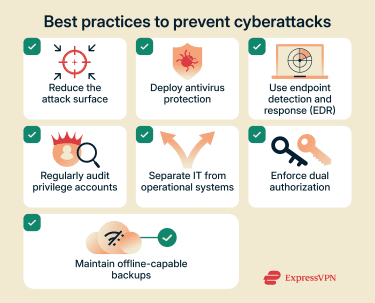

How to protect against advanced malware

Protecting against advanced malware starts with accepting that no single defense is enough. These threats are designed to hide, move slowly, and avoid detection, so security needs to be layered. The tips below can help strengthen defenses against different types of worms and other sophisticated attacks.

Cybersecurity best practices

Basic cybersecurity best practices still matter, even against sophisticated threats. These fundamentals help reduce risk and limit damage if an attack occurs:

- Rigorous patch and configuration management: While advanced attacks may use zero-day vulnerabilities, they frequently combine them with known weaknesses to move laterally or escalate access. Reducing the overall attack surface limits the paths available to a persistent threat.

- Traditional antivirus: Signature-based tools still play a role in identifying known malware components and preventing commodity threats from obscuring more targeted activity. They’re not sufficient on their own, but they reduce background noise.

- Endpoint detection and response (EDR): Behavioral monitoring on endpoints provides visibility into unusual process execution, privilege changes, and lateral movement, which are capabilities essential for detecting malware designed to remain dormant or blend in with normal activity.

- Strict privilege management and access review: Advanced malware often succeeds by abusing excessive trust. Regularly auditing privileged accounts and removing unnecessary access reduces the likelihood that a single compromise can reach sensitive or safety-critical systems.

- Role-based access control across boundaries: Clear separation between business systems and operational technology limits the ability of malware to pivot from general-purpose environments into ICS.

- Change control and dual authorization for high-impact actions: Requiring oversight for administrative or configuration changes reduces the risk that malicious or compromised access can quietly alter critical systems.

- Verified, offline-capable backups: When malware degrades systems gradually rather than causing immediate failure, reliable recovery mechanisms become essential for restoring trust in affected environments.

Training and threat awareness for staff

Stuxnet showed that people are often the first point of contact between malware and a secure system. Training helps staff recognize risky behavior that can be prevented before it creates an opening for a sophisticated attack. A well-rounded cyber awareness program should include:

- Understanding common cyber threats: Recognizing high-risk attacks such as phishing, data breaches, and social engineering.

- Knowing how to handle sensitive data: Understanding data classification levels and how confidential information should be stored, shared, and protected.

- Following security policies and best practices: Using company systems, software, and devices in a safe and approved way.

- Learning basic security safeguards: Understanding the core tools and controls that help protect organizational systems.

- Recognizing and reporting incidents: Knowing who to contact and what steps to take if suspicious activity or a breach occurs.

When staff know what to watch for and how to respond, they become an active part of the defense rather than an accidental weakness.

Monitoring ICS and SCADA environments

When monitoring ICS and SCADA environments, focus on spotting unusual behavior rather than waiting for systems to fail. Instead of only looking for malware, watch for changes in performance, timing, commands, and data flow. Small irregularities, such as unexpected command sequences or altered sensor readings, can be early warning signs of a problem.

Monitoring should cover all critical components, including the SCADA master unit, remote terminal units (RTUs), PLCs, and field devices like sensors and actuators. Unauthorized access or unexpected changes to any of these can directly affect physical processes.

Be alert to common SCADA threats such as man-in-the-middle attack (MITM), where communications between central systems and remote devices are intercepted or altered, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks that disrupt normal operations. Monitoring network traffic and communication patterns can help detect these attacks early.

To strengthen your monitoring strategy, use an intrusion detection system (IDS), enforce device authentication, and verify data integrity. Protect data in transit with secure communication protocols like Transport Layer Security (TLS) and Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). Regular security audits and network segmentation can further limit the impact of an intrusion, helping maintain the safety and reliability of ICS and SCADA environments.

FAQ: Common questions about the Stuxnet virus

What is the Stuxnet virus and why is it so dangerous?

Stuxnet is a highly advanced computer worm that was dangerous because it caused physical damage through digital means. Unlike typical malware, it was designed to manipulate industrial machines while appearing normal to operators, which made detection difficult and consequences more severe.

How did Stuxnet infect air-gapped systems?

Stuxnet infected air-gapped systems by exploiting human behavior rather than internet connections. It spread through removable media like USB drives and trusted internal computers, allowing it to cross physical network boundaries that were assumed to be safe.

What did Stuxnet teach us about cyberwarfare?

Stuxnet is widely regarded as one of the first known examples of a cyber operation with physical effects, often cited in discussions about the emerging field of cyberwarfare. While no official party has confirmed its use as a tool of state-sponsored conflict, the malware demonstrated how cyber capabilities can potentially be employed to disrupt critical infrastructure with strategic intent.

How can critical infrastructure be protected from similar threats?

Critical infrastructure can be protected by using layered security rather than relying on a single defense. This includes monitoring system behavior, limiting access, and training staff to recognize risks, all of which reduce the chance of a silent, long-term attack.

What’s the difference between a virus, worm, and Stuxnet?

A virus usually needs user action to spread, while a worm spreads automatically across systems. Stuxnet went further by being a highly targeted worm built to control physical processes, not just infect computers or steal data.

What are the global security implications of cyberweapons?

Cyberweapons present unique challenges for global security. They can be difficult to trace and may be used without public acknowledgment. This makes accountability and response more difficult and challenges existing legal and security frameworks.

What is air-gapping and is it still effective?

Air-gapping is the practice of isolating critical systems from other networks to prevent remote access. It’s still useful, but it’s no longer foolproof because people, devices, and maintenance tasks can bridge the gap, requiring additional safeguards to stay effective.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN